The indicated pages from the first chapter of The Book in Society familiarize the reader with the emergence of several writing systems throughout history. These systems include hieroglyphics (picture-writing), phonetics (speech-sounds), and third which combines these two systems. Robinson breaks these systems down into two groups: semasiographic (language based on signs) and lexigraphic (language based on words). While semasiographic language can be found throughout modern life, Robinson narrows her focus to the development of the type of language used for reading and writing today. Robinson recognizes the contributions of ancient Asian civilizations before and after the Common Era, namely, the invention of parchment, printing, and paper, which all helped to popularize book culture throughout the Eastern hemisphere. The codex, which Robinson describes as a “book with folded and sewn-together sheets that form leaves,” (34) was invented at the turn of the Common Era and soon became the prominent book format.

Around 400 BCE, the ancient Greeks developed their own writing system based on a number of pre-existing ones. With their addition of symbols (ie. letters) representing vowel sounds, reading and writing became easier and more accessible. Over the next few hundred years, the uniformity of the Greek writing system allowed for the development of critical theory and a better understanding of pre-existing texts (eg. the New Testament). There soon came a need for libraries, which helped to preserve books and therefore knowledge.

The second chapter of The Broadview Reader in Book History are selections from Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin’s book The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800 that specifically cover the evolution of how the book and how we have arrived at the modern book. Throughout this chapter the authors stress that all the progressions made to the book took a long time to be fully implemented after their invention. Most of the inventions begin around 1500 and the modern book starts to appear around 1800.

They begin by describing early books, or incunabula, that imitated manuscripts. Gradually, more styles of script were introduced and spread across Europe at different paces. Another feature that took many different forms during its lifetime is the title page. The authors describe how at first printers were simply trying to fill blank space on the opening recto. There then came a period where title pages were extremely elaborate and lengthy before they were finally simplified to what they are today. Febvre and Martin also cover the evolution of the size and format of the book, how illustrations were printed onto a page, and the bindings of a book.

This short section serves as an introduction to the history of printing and some of the different processes used to do it. One of the most useful notes from this chapter are the ways that ink is put onto the page: relief, intaglio, and planographic. There is an excellent graphic on p. 39 that illustrates how each were performed. Regardless of the method, the text and the images on the metal type being printed had to be reversed so they would show up the correct way on the page. However, Twyman names several different ways that printing images and text on the same page can be difficult, and it was not until the 19th century that the same technology was used to do both tasks.

Twyman dips into other topics such as multiplication (creating identical copies), types of paper and ink, and the coming of the power printing machine. At the end of the chapter, Twyman notes that while the history of the codex form is important, there are plenty of other media that have had their own evolutions, such as newspapers, maps, and legal documents.

Pages 82-100 of Robinson’s The Book in Society details several key innovations to print culture in its early stages. Robinson starts off before the invention of the print press with wood blocks, which were carved with basic words and images. Afterwards, Robinson details the invention of the press itself along with its inventor, Johannes Gutenberg. Steps like making the metal type, using the proper oil-based ink, and using the screw-press to evenly distribute the ink are all detailed in this section. Robinson says that Gutenberg’s model for the print press persisted until the nineteenth century with only a few improvements along the way.

Pages 93-97 cover the influence on various religious groups in both expanding and censoring specific texts. The Catholic Church took advantage of the new technology to mass produce their devotional texts. Only certain print shops were allowed to print the King James Bible to maintain a standard and prevent tampering. The Church also kept a list of books that were forbidden to be published, called The Index of 1569.

As the centuries go by, a wider assortment of texts are printed and circulated. Scholarly texts began to pop up during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, including the Principia Mathematica by Isaac Newton. The popularity of his books helped to fuel the need for scholarly texts to become more available.

Johns’ main point throughout his article is that early books were not as openly trusted as we trust our own books. Johns counters Eisenstein’s earlier argument that fixity was one of the most important things that print culture brought to the world at the time by saying that these books were not identical like we assume they would be. Piracy and censorship played a big role in causing readers to be skeptical of the written materials, seen in the example of Galileo’s Dialogo (censorship). It was not impossible to fact-check these sources and trace where the book came from, so knowing who made the book had a lot to do with how valid its information was. Johns says on page 282 that “the first book reputed to have been printed without any errors appeared only in 1760,” really demonstrating how long it took to actually achieve fixity.

I found this author and the last author quite difficult to engage with, coming across as almost egotistical. Both Johns and Eisenstein act as if they are the only ones to ever have these ideas and talk down on the way people (and critics) approach print culture. Instead of trying to educate and explain the importance of print culture and its many aspects, they turn off the reader by exclaiming their superiority. This is not to discredit their ideas, but their attitudes are off-putting.

Robert Darnton takes a different, more formulaic approach to book history, but still argues that it is a massive field of study that we often do not acknowledge as a whole. Book history emerged out of several historical questions that could not be answered without investigating the impact of early print culture. He argues that the field is so large and composed of so many different specializations that researchers often lose sight of the bigger picture. This bigger picture often includes the reader themselves, as they can influence later editions by the authors.

Darnton says that the general pattern for the life of a book is like a communications circuit from author to publisher, from publisher to printer, from printer to shipment, shipment to selling, and finally ending with the reader, who loops it back to the author. Darnton demonstrates the usefulness of his model by applying it to Voltaire’s Questions sur l’Encyclopédie and therefore:

showing how each phase is related to (1) other activities that a given person has underway at a given point in the circuit, (2) other persons at the time point in other circuits, (3) other persons at other points in the same circuits, and (4) other elements in society. (234)

Darnton has a diagram for his model on page 234 that shows the connection between all these elements. By the end of the article, he has shown the effectiveness of his methods.

Chartier focuses mainly on the practice of reading and how it has been, for the most part, ignored by critics of print culture. He links the relationship between reader, text, and print by showing how both content and form change the way texts have been interpreted. Chartier makes it clear early on that it is the reader that gives a text any meaning through their analysis and use. The same text can be read by different people in different ways for different purposes, and a different message can be derived by both readers. When reading was generally done aloud, texts were written with that delivery in mind. Chartier notes that those who were read to (and their interpretations) are often not accounted for when researching the history of print. He therefore neglects to categorize readers simply by their socio-economic class and strays away from statistics on literacy rates.

In addition, Chartier accounts for the gradual process texts went through to become more accessible, such as adopting paragraphs and indents, simplifying texts, using illustrations, and repeating the same images throughout multiple texts. To Chartier, the impact of form on a text is substantial.

The indicated pages are dedicated to the topic of selling books and how different kinds of organizations have influenced each other over the past ~100 years. There is a brief history of early book trade, but the main focus is contemporary bookselling. Robinson does a lot of comparison in this section, namely, the differences between selling new and used books, selling books out of an independently owned store or a big box store, selling books to consumers or collectors, or selling books in a store or online. The introduction of chain stores and wholesale stores threatened local businesses, but they were able to adapt and survive by providing services and holding events the corporations cannot.

Companies like Amazon.com have completely changed how we buy books. The selection is unlimited and ordering a book to your house is convenient, but has monopolized the industry and prevents a lot of growth. However its done, selling books is essential to the entire process of getting an author’s ideas into the hands of a reader.

Robinson goes into detail and provides a lot of examples of copyright law and censorship from the early days of print to modern day. Copyright law is put in place to protect content creators from having their intellectual property stolen. These laws vary from country to country, which can be difficult when information crosses these borders. One country may have a ban on a certain book (ie censorship) while another may celebrate its ideas. The Church participated in quite a lot of censorship.

In addition to prohibiting material, certain states may use literature to their advantage. During World War II, books were both burned and used to convince people of a certain ideology. Propaganda ran rampant, often trying to recruit people to the war or promote war bonds. Though these are only a few examples, Robinson provides many in this section.

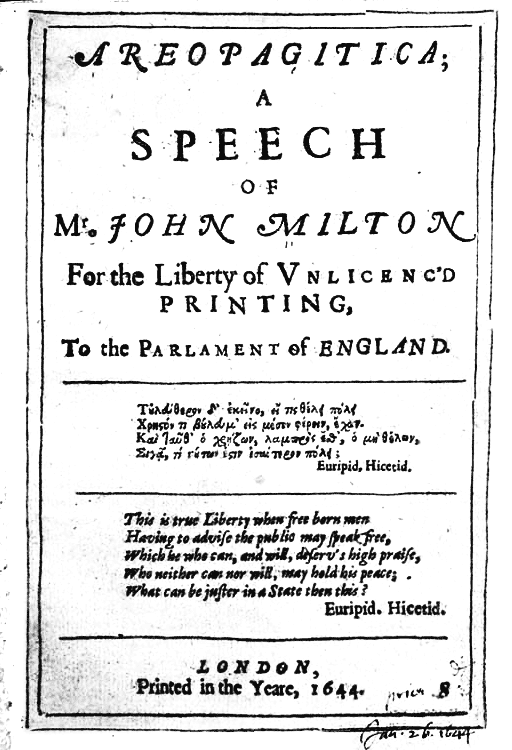

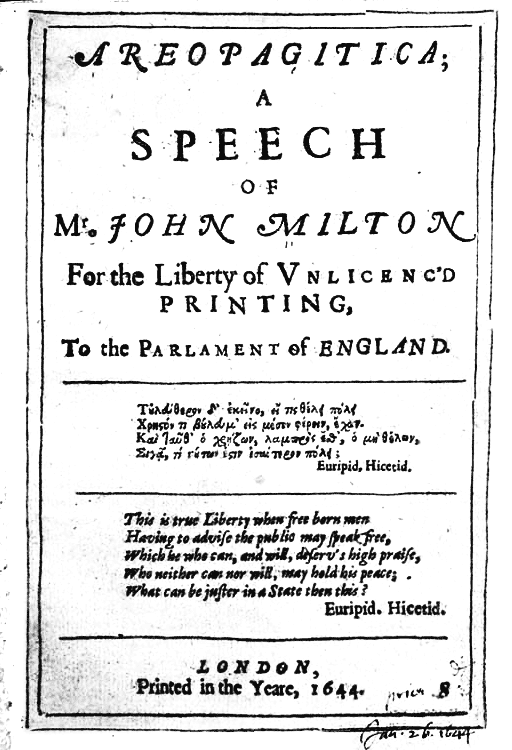

Milton raises several concerns with new censorship laws in his essay Areopagitica. One of his main arguments against these laws is that censorship works better after the works have been released to the public and allow them to interpret the text. Milton uses examples from ancient Greece and Rome to demonstrate how this method is superior.

Milton is quite passionate about this topic and his voice throughout is incredibly powerful and rhetorical. He says that “hee who destroyes a good Booke, kills reason it selfe, kills the Image of God,” showing just how much he believes it is up to the public to evaluate text. The act of reading - whether the books are good or bad - enter us into a more thorough understanding of the topics, and to have others select what we should read can close us off to different ways of thinking.

Greg believes that by dissecting the physical forms of a book through bibliography we can understand more about the content. Greg distinguishes between descriptive and critical bibliographies starting on page 5, and although he argues throughout that bibliographical studies should be treated like a science, he says descriptive bibliographies presuppose a relationship with the sciences. Greg stresses that establishing this scientific approach to analyzing texts is what will help further the field of book study and open our understanding of specific texts.

Greg deals with the issue of which editions of a book should be consulted when creating a new one. Greg says there are two kinds of changes an editor can make: substantive (substance) and accidental (not related to content) (128). It was generally believed that the first version, or manuscripts, should be the main authority, but Greg says that changes made by the author in later editions should trump earlier decisions. Greg admits that it can be tricky to know exactly what decisions to make and is simply trying to start a discussion on how to come together and create a more uniform process of editing.

Tanselle extends on Greg’s concept of what an editor is trying to accomplish, and that is to create a text that most accurately represents the author’s intentions. This chapter spends its time defining what an author’s final intentions actually are and what happens if they are not clear. It can be difficult to distinguish between edits that an author has made themselves and edits made by someone else. The process of discovering an author’s true intentions involves a lot of research outside the text, such as on the author’s biography and their entire works, in order to better understand what the author was trying to say. Tanselle says that “the editor finds himself in the position of the critic,” (144) when investigating intentions.

Tanselle’s definition for intention comes from Michael Hancher’s “active intention” - “‘the author’s intention to be (understood as) acting in some way or other,’” (142) which is the intention an author has while writing the text; what makes them choose one word over another. Understanding active intention in relation to the role of the editor is the main takeaway from Tanselle’s essay.

In his essay, McGann argues why it is easier and better to preserve text online, and in what areas this fails in physical book-copies. McGann says that when creating a new edition of a book, try as we may, it is impossible to preserve the physical appearance of the original edition. This discontinuation in representation from book-to-book is the book’s great weakness. He spends the next section of his essay discussing the advantages of modern technology to editors, who can now use images, sounds, and other tools to emulate a text, called a hypertext. It follows that this improvement in technology will create an improved understanding of the texts we study while maintaining a continuation in representation.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “How We Read: Close, Hyper, and Machine.” The Broadview Reader in Book History. Ed. Michelle Levy and Tom Mole. Broadview Press, 2015. 491-518.

Hayles addresses the issue of declining reading skills in young adults, but points out that they are reading more. She asks “how to convert the increased digital reading into reading ability and how to make effective bridges between digital reading and the literacy traditionally associated with print,” (492) at the beginning of her essay before exploring ways that people are engaging with text. The first way is close reading, which she says is on the decline and has been challenged for sacrificing affect, pleasure, and cultural understanding for a more literal understanding (495). The second and more spelled out way to read is digitally, or hyperreading. Hayles says that readers have less concentration when hyperreading, require constant stimulation (497), and retain less information (498). She briefly describes machine reading as similar to a word-frequency list capable of identifying patterns that close reading may overlook (504). She says all have their advantages and being able to teach and learn all three would greatly benefit a twenty-first century reader.

Grafton envisions a Universal Library where any and all texts can be accessed. While some scholars have been reluctant to accept digitized texts as a way to accomplish this, Grafton offers up both the strengths and weaknesses of having companies like Google. Google acts like footnotes in the way that it shows “where most people have gone before you in order to learn what you want to know,” (561). Grafton acknowledges that modernized reading has made it easier for more people to access more information (562), but we are unable to verify the authenticity of a text if we do not have access to its physical form (567). Hyperreading has also allowed for more texts to be produced and published (568). Grafton concludes that a reader should be able to navigate their way through both a search engine and a library in order to achieve the highest possible understanding on a topic.

The Book in Society

The Broadview Introduction to Book History

Areopagitica