This chapter discusses the early emergence of both writing and writing tools, focusing on the development of language and the systems and tools used to write books. This chapter introduces the book, and talks about the early writing systems. It follows the development of language, starting with Arabic script and going into the development of the current alphabet. The chapter also follows the development of writing tools, specifically modern-day paper, and discusses early forms of paper such as parchment and then into modern paper and how these early and modern forms are made. The chapter also discusses how all of these advancements influence literary movement in the world. Overall this chapter is a good broad introduction to the development of language and the book, and is presented in a way that is easy to read. The information is easy to find within the chapter, and would be a good source to learn the brief early history of the book.

Both sections begin by introducing the author and explaining why they were important to the study of book history and print culture. The first section looks at specific aspects of the book and how they’ve changed or were first produced (type fonts, the title page, the colophon, the printers mark, the format of the book, illustrations in books and the binding of the book). The second section focuses more on printing (how things were printed). Within this second section, “printing” is defined. This second section looks at origination (first stage) and Multiplication (second stage), how printing words differs from printing picture and how printing as a concept is not reserved for books and includes other printed works such as newspapers. These two sections offer a good look as the evolution of the book and printing, and is resented in a concise simple manner, which makes the receival of the information quick and effective. This is a valuable source.

In this section of reading, it begins with discussing the transition from scribal culture to print culture. It proceeds to go into detail on Gutenberg, and all of his inventions and things he had worked on (metal type, ink, ink balls, press, Bible, Latin Psalter) and how these inventions worked to make a page or book, as well as how these inventions affected Europe and the culture. It discusses how members of a singular religion did not agree with the way the religions ran, so they broke away from the singular and created multiple different religions. and how this increased religious printings. Protestantism was a big user and influence of the printing world. Vernacular Bibles were made in mass, and subsequently banned by the Roman Catholic Church, as they were trying to control what was put into the world and what people had access to. Lots of Bibles were made translations from Latin so that everyone could read and could study the religion. This reading ends with the enlightenment, a movement as a result of scientific books being published (Principia Mathimatica). Through out this reading, there are brief interruptions, in which key parts from the main text are briefly discussed (Biblia Pauperum, Type design, Gutenberg Bible, Officina Plantiniana). This section of reading is a valuable source, as it goes into great detail about the beginning of printing, and how the world around it affected what was produced.

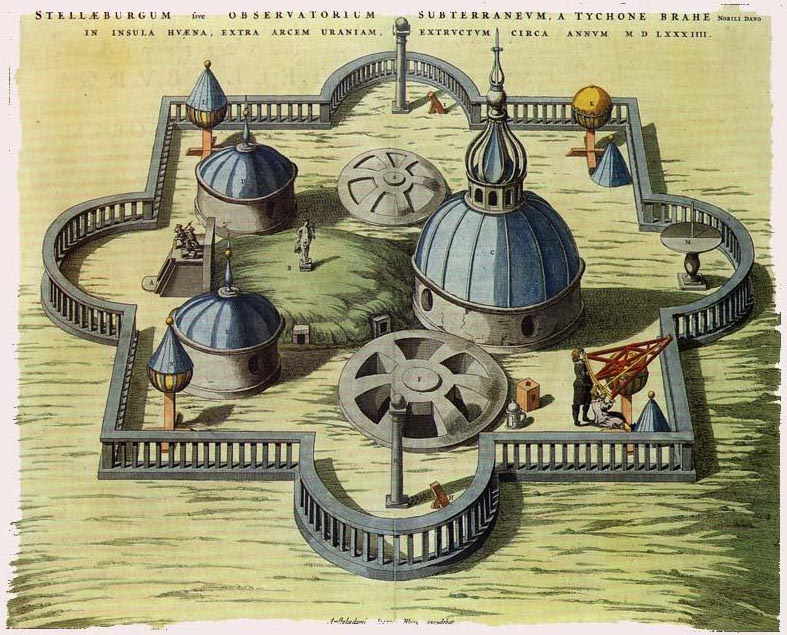

This is a response to Eisenstein’s work. He argues that what she said about the invention of printing is wrong, because printed copies were not all uniform and identical at the beginning. His chapter starts by describing all the parts of a modern book that we can trust to be there and that are expected. Piracy was bad in the beginning and threatened books. Tycho Brahe made an observatory, and printing press, and produced many materials that many people (royal or university) enjoyed, until after his death, and Johns uses him as an argument against Eisenstein. Follows into Galileo and how he produced a vastly popular book. Johns uses fixity as a big reason why Eisenstein’s theories were incorrect. Overall, this reading is very useful, and contains lots of information on not only his way of thinking, but also Eisenstein. This is a valuable source and should be used.

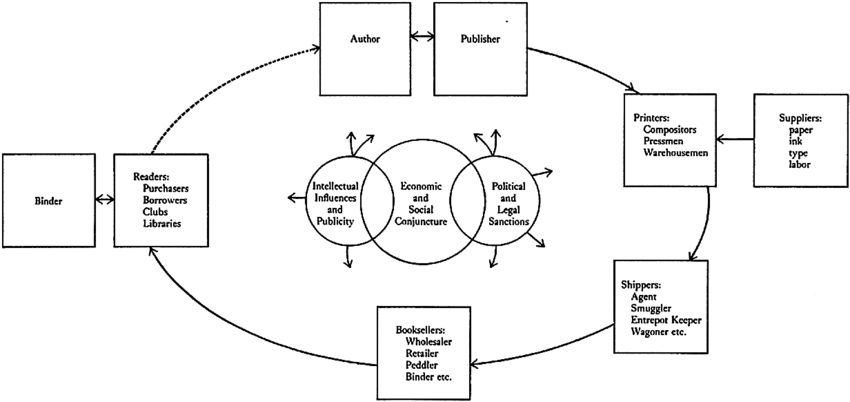

Begins by introducing Darnton and what he is going to do in this section (introduce “communications circuit” and show his way of studying books). He begins by saying that history of books is also understanding how thoughts and ideas were made into books and how these books affected mankind. Discusses how books started and why. Says that there is a circuit that book printing follows (from author to reader and lot of off branching parts), and you can’t just look at one part of it; you need to look at the whole. Darnton uses the publishing of Voltaire’s Questions sur l’Encyclopédie as an example and focuses on the bookseller (goes into great detail). Proceeds to go into further detail about the history of book circuit looking at each part (Author, publishers, printers, shippers, booksellers, readers). This section is very informative and gives a lot of information in a compact way, and with his example of Questions he puts his theories into an example and makes them clearer. This is a valuable source.

This reading starts by referencing the Darnton essay and his main point. Continues into talking about Michel Foucault and how he described where and why authors came into existence. Defines author by saying they create something new, identifies as an author, and writes for an audience. The first main part talks about the rise of the modern author, and discusses patronage (what it was and how it worked) and anonymous/pseudonymous writing (why and when someone would do this. The second main part talks about the profession of being an author, and discusses how authors moved away from patronage, legal issues of being an author (copyright and contracts), financial support authors got, as well as subscription publishing and royalties. The third section talks about professions arising from authors (agents), and discusses what a literary agent is and the different associations that provide support to the writing industry (and why they exist). The fourth section talks about transformations of an initial book, and discusses translations to different languages, adaptations to different mediums and the beginnings of the use of audio. The fifth section talks about self publishing and discusses its pros and cons and how/why an author would do it. Dispersed among the main sections are branch off topics, which include: William Shakespeare, the royal literary fund, Eudora Welty and Diarmuid Russell, pen international, and Bapsi Sidhwa. This reading is very useful, as it includes lots of information on a variety of factors that affect authors. This is a valuable source.

The introduction starts by saying that just as paperbacks changed the book world, so too did television and other mass media products. Bigger book stores took over and overwhelmed smaller ones. The most important development to book history was the computer (Project Gutenberg was the first website to have a huge election of digitalized books). Online libraries and book sales overtook physical ones. The first main section looks at literacy, and how the development of literacy rates, and schools, affect the supply and demand of books, as well as how more people were demanding books and were wanting to read. It discusses briefly libraries and their development (more in ch.9 if needed). Introduces periodicals (small prints such as newspapers, poetry, recipes…). The second main section looks at paperback books, which were a result of trying to lower the price of books. Goes into talking about paperbound books (Albatross books, Penguin books, Pocket books). The success of these companies sparked others to start creating cheaper options as well. The success of paperback books helped certain genres of books to grow and flourish (detective fiction, science fiction, western, romances), and more detail on these genres is included. Compares Mass Market and Trade. Within the two main sections, two smaller topics are discussed in their own part (The Saturday Evening Post, Penguin Books). This section of the chapter is useful and informative, as well as easy to read and interesting. A valuable source.

Begins by introducing entities that have influenced book history (rulers, states, churches) and how they have had a strong influence. This section looks at religious and civil authorities and their part in book history. The first section looks at the regulation of print: regulations were put in early on to protect church and state from any harmful (to them) material being printed. Many of these regulations were caused by strife within religions and states. Bans on foreign books appeared, and pre-publication laws required books to get approved before publishing. Specific taxes (and other added costs) could be placed on books increasing the final cost. The second section looks at censorship: censorship is the prevention of books being read. One of the first instances of international censorship came from the Roman Catholic Church in 1515 (explained in detail). Churches had religious censorship, but the state also censored readings. Readings could be considered treasonous or seditious, anything that could be read as an opposition to the state or gave ideas that the state didn’t agree with could be banned. The section goes into talking about the modern era, and the censorship during the holocaust, as well as censorship after/during wars and in the United States. The third section is about promoting print: who is allowed to print and distribute books is looked at. Freedom of the press is introduced, the history of copyright is given (in detail: places, people, books) in both an early and modern sense. Introduced copyleft in relation to copyright. The fourth section is about Harnessing Print: government moved from only controlling what was allowed to be printed into using printing for their benefit, propaganda being the biggest use to the government, particularly in times of war. Within this chapter, smaller topics are mixed in: Book bans and challengers, Obscenity Legislations and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, and The Danish Cartoons Controversy. This section is a very useful section and gives great detail into censorship and ow it came to be, the evolution of it. This is a valuable section.

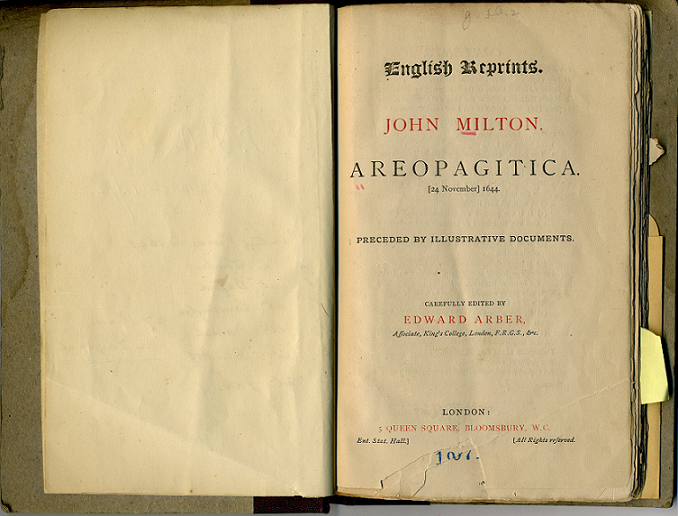

This is a speech to the high court for the liberty of unlicensed publishing. Starts by listing opposing matters. Says that if this were to work it would be due to god (and some flattery of the court). Lists three principal things of courtship and flattery. He says not to brag about your accomplishments. He says he understands that the church and the commonwealth would have a concern as to what is being printed, but stopping a good book from being printed is almost the same as killing a good man. Starts to compare to Athens were books were important and not as censored. Discusses a few cities in Greece that experience censorship (or lack of) and how it worked: he uses specific examples. Examples include philosophers, emperors, churches, biblical characters (Moses, David, Paul, Adam), the law, poets… he says that the bible itself has blasphemous writing because people will make their own good decisions by reading about the bad. Refers to Plato often in different contexts. He says that you also need to consider the quality of the man doing the screening and censoring, that it can not be just anybody. He says that learning is a value to men and should not be taken away. He says it is an insult to the churches to say that their preaching isn’t good enough to combat a book that could tempt people. He thinks people should be able to read bad things and make their own choices so that when they do make the right choice it is true. He makes many good points in his speech, and while it is an interesting read, the language makes it harder to read, and as such there is the concern for misinterpreting what is being said or missing something important, so this would not be a source to reach to at first.

Begins by introducing Greg’s accomplishments in the field of bibliography, and also introduces the essay, in which he introduces a need to a scientific bibliography that matches scientific needs. Greg talks about the difference between a descriptive and a critical bibliography, and these two types are described in detail. The essay begins with discussion the evolution o bibliography. Greg discusses the influence of bibliographical pioneers and how they created the field, but expresses his disappointment in the artistic aspect of the field. He seems to relate bibliography more as a science, but still not quite up to par with actual science. It is a descriptive science, and he refers to it as a science because it is the gathering and organizing of fact (bibliographies). Greg says that he believes that many people think that bibliography is solely the study of printed books, and therefore would not relate to things such as manuscripts. He says by looking at bibliography as scientifically, you can apply the methods to any form of writing (printed books, manuscripts, clay cylinders, rolls of papyrus, codices), and it is this method of examining that defines bibliography, not the object that is being examined.

Greg stresses the importance of looking at certain elements of bibliography (how a sheet of paper is folded for example) and can’t only focus on the description or cataloging of the books. The book itself is what is interesting, and examiners of the book must be focused on things outside of its description. Greg states that examiners of books (bibliographers) would be specialized in one aspect most likely, but should know about all of the important elements: typography, paleography, watermarks, methods of printing and binding, practices of publication and selling, and book illustrations and illuminations. He follows by going into more detail on typography (and a bit on paleography), and says that for these reasons (the elements that are important), it would be very wrong for bibliographers to exclude manuscripts.

Greg starts to go into details on descriptive or systematic bibliography, giving a definition for it. Greg talks about what is considered and “ideal bibliographer”, and how he feels about the idea. He says that a bibliographer is not concerned with the contents of a book, but rather the putting together of said book. He reaches what he truly wants to talk about in this essay, which is the critical bibliography. Greg says that his interest in bibliography stems from an interest of literature and he stumbled into the field as he was searching for more information on books, and Greg says that he values the field and finds it important.

Greg includes a quote from Dr. Copigner that he finds valuable, but that he says has been misunderstood. Where Copigner says that bibliography is the grammar of literature, Greg says it is the dictionary. Greg now moves back to critical bibliography, and gives his definition for it, in which he describes it as a science once again. He says that this is not a new science, and Greg describe why editors would struggle more than bibliographers on the topic. He criticizes editors in their abilities and what they focus on when it comes to examining books.

Greg finishes by describing a dream he had, in which he described a lecturer giving a lecture on bibliography. He says that the lecturer will begin with the general principals of textual transmissions, he will describe how manuscripts were made, he will look at the influence of manuscripts and he will look at textual criticism. Greg says the lecturer will look at individual moments of literary history, he will look at the evolution of manuscripts, the decay of certain systems and he will discuss the three Visions of Piers Plowman. Greg says that the lecturer will introduce printing, editions, composition and imposition, type, and false imprints. The lecturer will look at the relationships between author, publisher and printer, he will discuss copyright, folios, and styles of editing.This section/introduction is a valuable source. It was easy to read and it was personal, and shows Greg’s opinion on the subject of bibliography.

This section begins by introducing Tanselle by saying he has written extensively on textual criticism and bibliography, as well as being an editor and a professor. It states that editors usually follow the authors intentions and finale revisions, but sometime that is not possible. Introduces what Tanselle will be talking about: three kinds of intentions (programmatic, active, finale), two kinds of revision (horizonal and vertical), and two kinds of attitudes (embrace or acquiesce).

In the introduction of his work, Tanselle says that in general, the job of an editor is o discover what the author wrote and what it should look like when it is published. Relates back to Greg (the rationale of Copy-text), where he generally agrees with what Greg has said, but Tanselle says that Greg did not define what and author’s intention is. When this idea is related back to editing, it does not mean that an editor’s task is not to improve on the work of an author, but more towards understanding what the author means. The authors intention is often understood as the last revised version of the work, although this does not work in two cases: the first being when the editor must decide f the changes were authorial alterations, or alterations made from someone else, and the second is when the editor must decide if the changes made by the author truly reflect the author’s finale intention.

In the first section of this source, it begins with Tanselle stating that if the editor wants to publish a text as the author wants it, he has to consider if this version truly presents the meaning of the book to the public. The editor can not just reproduce the book without thinking about it, because sometimes the author makes a mistake that they do not want in their work. Making changes for the author helps with clarifying the intentions of the author. When talking about intentions, Tanselle introduces the kinds of author’s intentions. The first is programmatic intention, which is the author’s plan to write the text. The third is final intentions, which is the authors hope that the text change the readers viewpoint or make the author wealthy. The second is active intention, and this is the one that is concerned with the meanings within the work. Hancher (who proposed these three types of intentions) says that the first and the third types of intentions are irrelevant to the interpretation of a work, but that the second type is very important when analysing a book. Tanselle says that Greg and Hancher would not agree with the definition of “finale intention”, but most editors use Hancher’s view. Tanselle goes to talking about how an author intended meaning is discovered, and the sole goal of an editor is to discover the true meanings and intentions of an author. Tanselle says that editing is a critical activity and the editorial freedom in editing is his knowledge of the author.

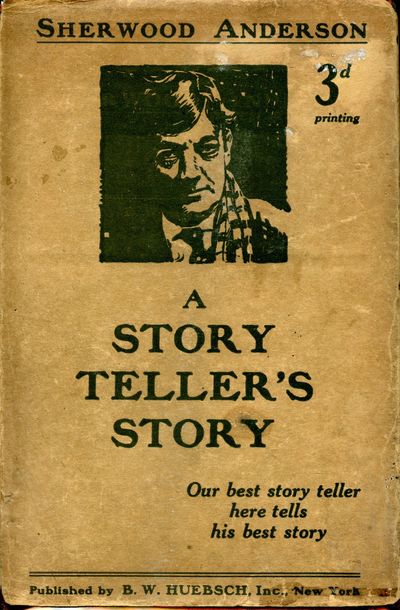

The second section of the text is interested in authorial intention. The editor must decide if a change made is done so by the author or by somebody else, and while doing so, must also decide that if these changes are made by someone else, are they still good changes. This situation is illustrated by Anderson’s “A Story Teller’s Story”, where the only surviving version of a text is revised by three people. The copy printed however, has changes not made by the original three people. Deciding what the true changes that should be made can be done by looking at history and taking things like the authors letters to people into consideration when looking at who made what changes. After the editor decides which changes are the authors and which are made by other people, they must decide the status of the other people. They must decide whether to keep the changes made by other people or reject them. A question arises if an author can ask someone else to carry out their intentions within revisions. By definition of an author’s active intentions, the author can not do this. But the author can accept what someone else has done.

The third section starts with what happens after the editor has separated authorial from non-authorial alterations and how they are going to continue with the editing of the text. Now being looked at is the two situations where the view of finale intentions does not work: when the revisions produce a new book rather than a finale version, and when the author lets new material into their work in later editions of the work. In the first case, the author may choose to alter the text so drastically for a reason, such as making a condensed, children version of the work, in which case making it new. An example of an author who condensed and changed his works is Henry James (goes into details). Goes into why the quantity of changes made should affect the work. There needs to be a distinguishing between how many changes can be made before the editors accept the changes as being a new work altogether. There are many examples of different authors who have changed or wanted to change that follows this question.

The last section is interested in two issues of editing: the first is what does intentions signify and is it finale, and the second being does it matter whether the authors working is recovered when amendments made by others are better. The second question was easier to answer (and it is), but the first is what this section is about. Intention is too complicated to define, but authorial intention is not as simple as the author stating their intentions. It is a harmony between the editor and the other where the intentions truly arise.This section repeated itself sometimes, but as a whole was useful in it having many examples to back up the information.

This section begins by introducing McGann, and how he brings his knowledge of bring a textual editor and editorial theorist together to show the potential of the digital world in relation to editors, specifically regarding the hypertext. McGann’s essay here is a response to Greg’s essay (The Rationale of Copy-text), and will explain how the digital world makes copy-text no longer necessary.

The introduction of the essay introduces the main topic, the physical character of a literary work (audible and visual), and how he will be looking a why these are important, and explain them. He states that his words only refer to scientific works, as poetical writing is very different.

The first section is titled “The Book as a Machine of Knowledge”. McGann begins by asking the question ‘why’, and saying that all literary works resemble a book in some form, although literature itself has drastically evolved over time. McGann uses the example of the Oxford English Dictionary to show the limitations of the book and the power of the electronic version. He also begins to examine the trouble with codex tools, and how it is difficult to study books using books. Problems arise such as knowing which book to use and when the reader is wanting information beyond what is found in the primary work. McGann introduces archives and indexing, and how hardcopies of information limit the spread of information. Computerization of hardcopies allows anyone to read the book.

The second section of this essay is titles “Hyperediting and Hypermedia”. Hyperediting is electronic, and it solves codex-based limitations. It edits on a different level then humans. McGann introduces hypertexts as well and shows how they are useful in editing. Hypermedia becomes a thing when audio and visual documents are introduced. McGann introduce the limitations and problems associated with these ‘hyper’ items, and explains how all three of these hyper-items must be used cohesively and with reservation to achieve optimal results and not miss anything.

The third section is titled “The Necessity of Hypermedia”. McGann shows the need of hypermedia through example of poems in New Oxford Book of Romanic Period and the book itself. McGann wanted to include illustrations for these poems, and he talks about the important of color facsimiles in reference to the understandings of the poems. McGann calls the New Oxford a reader’s edition, not a critical one. McGann compares this book and its poetry to Robert Burns’s poetry and how both pieces were published. He says that these two examples could stand as paradigms for a whole range of materials. McGann begins showing how Blake’s work developed poetic literature in how poems were being published and perceived, and how the book itself is a limitation for poetry, but hypermedia might allow Blake’s work to be published in a proper way. McGann then moves into talking about Emily Dickinson and how her poetry has been published. McGann says that on top of the literal meaning of the words of Dickinson, the visual representation of her work holds just as much meaning.

The fourth section is titled “Conclusion: The Rossetti Hypermedia Archive”. This section is focusing on hypermedia and hyperediting once again. It begins by showing how hyperediting causes a problem when it comes to incorporating digital images into the work. McGann begins to use the example of the Rosetti hypermedia archive. Those who worked on the archive needed to do two things: design a tag for the physical features of the documents, and develop a tool that would let them attached these physical features to images. McGann briefly shows the limitations of an edition vs an archive using the Rossetti. In the modern period, there is a focus on displaying to the best of the abilities all of the work of an author in a manner which reflects the work the best. McGann says the switch from paper-text to electronic is the same impact as the switch from manuscripts to print.

The last section is titled “Coda. A Note on the Decentered Text”. In this section, McGann takes a stand that hyperediting does not require a central text for organizing the hypertext of documents. He compares hypertext to movable script to show its impact. He says that hypertext is highly structured, and that hypertext is constantly being changed and improved, and this change is what makes it different from standard books. McGann then makes reference to the fact that the internet, the ultimate archives of archives, was designed as a decentered structure, which allows information to be destroyed at any time. With hypertext, all documents can be connected to each other. McGann then refers back to The Rossetti Archives once again and shows how it follows a decentered theme. He once again compares books to the electronic versions, and how decentralisation fits into these ideas.This section is very interesting and shows a unique aspect of the digitization of books.

The section begins by introducing Hayles. She is a professor, and has degrees in both chemistry and literature, and she works a lot on the technical and digital side of book history. She is working to describe the relationship between the digital world and humans, and how this world is changing how we read and explore literature.

Hayles begins her essay by saying that people I general are reading less printed material and are reading more from a screen, and the reading abilities of the population is declining. Hayles says that the NEA has called this correlation between people reading less print and doing it poorly is a casual correlation, and that reading opens a lot of doors and is healthy. This casual correlation is concerning. The NEA says that while print reading in general has decreased, recently there has been an increase in novel reading, as well as digital reading. The question is posed on how to make the increase of digital reading also cause an increase in reading abilities.

Hayles’s first main section of her essay is titled “Close Reading and Disciplinary Identity”. Hayles says that close reading was a response to print literature changing from classical literature to magazines and less cultured printings. She says that Jane Gallop says close reading turns reading into a profession, as it is a skill learned in classrooms and from practice. Hayles also introduces Barbara Johnson, who says that close reading is the only thing that can be called literary. Hayles says that most people think they know what close reading is, but that it is actually much harder to define, and she gives a few definitions from the professionals. Hayles compares it t symptomatic reading, but says that people are growing tired of symptomatic reading.

Hayles’s second section is titled “Digital and Print Literacies”. Hayles proposes that we can not push digital reading to the side in favor of print reading, but instead must focus on both and the same time and look at how we can improve both. Hays introduces Vygotsky, and how he says that the bridge between print and digital reading must be closed, and how teachers must look at the skills of the student at where they are beginning, not where they want them to end up. Hayles next introduces James Sosnoski, who introduced the concept of hyperreading, which is a response to computer reading. Through research, it was determined that digital reading can be sloppy, which allowed researchers to figure out where the best place to put the important information is and where it should not go.

Hayles’s third section is titled “Reading on the web”. In response to the digital movement of reading, it was shown that hyperlinks tend to lessen the understanding of the reader instead of increasing it, and the more links found the less comprehension received. It can be concluded that print versions of the same material are better understood that written online with links. Carr says that this is because of working memory. Research done by a French neurophysiologist showed that when illiterate and literate sisters were compared, the literate one had a stronger ability of phonemic structure of language.

Hayles’s fourth section is titled “The Importance of Anecdotal Evidence”. She begins by saying that professors are no longer assigning books, but rather chapters and excerpts because students will not read the books. Hyperattention is introduced, and it is the cause for this lack of book reading. Hyperreading is more associated with computer reading. It is suggested also that com0uters themselves can read, and that this ability for computers to read is useful and should not be undermined. There are misconceptions about computers reading. Hayles goes on to show the relationship and differences of close, hyper, and machine reading. Patterns are discussed due to machine reading needing to follow certain patterns. Meaning is brought into question, as the same sentence could be read two different ways and have two meanings. Machine reading can find patterns in a work which add to meaning that a human would not find. There are advantages and disadvantages for all three types of reading.

Hayles’s last section is titled “Synergies between Close, Hyper and Machine Reading”. Literature is introduced and an example is given on how this method is useful for students reading. Students took “Romeo and Juliet” and turned it into an online Facebook war, connecting the digital and the print world to enhance the understand of the play overall. When hyperreading, students were found when reading online to skim over the text rather than read it. Hayles states that the three types of reaching introduced should not be used exclusively, but rather cohesively to adapt to the modern world of reading and to get the bet understanding of a work as possible.This section was very useful in showing how close reading came to be and the importance of it.

This section begins with introducing Anthony Grafton, a professor at Princeton, and gives a list of his accomplishments and interests, ending with it saying that Grafton writes many articles on the impact of technology and the future of universities. This beginning section introduces the following essay, saying that it will follow the path of scholars from the renaissance to the modern day, looking at their use of the printed book and the university that they study how, specifically how these universities host the books. The section introduces the Google Books digitization project, and gives a few reasons why Grafton thinks it will not work (ignoring early books, metadata, no access to physical forms of the books for examination).

Grafton’s essay begins with his introduction. Here is introduces Aldred Kazin and his book On Native Grounds. Grafton tell the story of how Kazin became an author, starting at a school where his teachers did not care, and finding passion for literature at the New York Public Library. Grafton says that the internet and computers have changed books dramatically, and books have gone from symbolizing the end of the world to the world being the end of books. As trees die so too do books. Grafton himself presents Google Books, and says that those involved in the printing of books are fascinated by the possibility of a digital library where all information can be found. Grafton then goes into talking about his love for libraries, but he can not support those who argue against the digitization of books.

The first section of Grafton’s essay is titled “The Universal Library”. He begins by saying that the internet will not make a universal library, and it will not wipe out print literature, as magazines and books are still selling lots of copies today. Grafton continues into talking about how books were produced and organized in the past. He says that the scribes and scholars who made the books were typically the ones who organized them as well, but that is no longer the case. He introduces the Library of Alexandria, and Grafton gives a history of the library and talks about how it is similar to what Google is trying to do.

The second section of this essay is titled “Google’s Empire”. Grafton starts by showing how the internet has changed scholars, and how scholars no longer go to a library for information, but rather go online searching. Grafton examines the beginnings of Google, and shows how it has evolved into its current state. He examines the online market of book selling, and how the majority of the book market begins online, whether it be digital or physical books the buyer is searching for. Grafton introduces many of the online sites that currently have books available for readers online, and how useful the online libraries can be for readers, who can have any information they could want found at the touch of a button. Grafton then continues on to talk about world poverty in relation to books, showing how many people do not have access to information, and how the internet has not done much to address this problem. Grafton then returns to Kazin, saying that Kazin loved the New York Public Library because anyone and everyone could go into it. Grafton talks about how people fear that Google’s library will be only English, but Grafton says that more than half of the books published are English, so there will be much English in the library, but the more libraries that sign on with Google, the more languages and texts will be digitized. Graton then introduces problems that are being found with Google’s library, from how to books are scanned to how people can search and come up with wrong answers. These problems are also affecting the metadata. Grafton compares Google to the Widener Library to show the success and limitation of Google. Grafton says that a large problem for the Google Library is copyright. Grafton talks about Google’s reasons for ignoring the early books in their library. Grafton also says that for the time being, physical libraries are irreplaceable. If a universal library were to exist, it needs to be available to everyone and have little limitations. Grafton says that even if a universal library becomes possible, researchers will always need physical books, and the physical side of books says a lot about the history of books, through its printings and bindings etc.

The third section of this essay is titled “Publishing without Paper?”. Grafton says that it is not only researching techniques that are changing, but the publishing industry as a whole is changing as well. He says that scholars are no longer bothering to go to a library to do research, meaning articles that are digitized are not read as much. This has gotten so drastic that many companies and publishers are making authors publish online as well as physical. The online publishing offers a more interactive learning to readers, and can include much more freely images to enhance learning. Critics however don’t like the emphasis placed on design of online resources rather than content. Grafton then goes into comparing the modern news outlets to old published ones, showing the similarities and the differences. By having online resources of printed material, readers can access things in Britain and New York from their own homes. Grafton talks about how many cities are building central libraries, in an effort it seems to make sure books do not go unnoticed, and so that libraries do not go extinct. Grafton shows how reading itself however is become less and less prevalent in the minds of young people, and they are choosing to read less than to read for enjoyment and in-depth learning.

The last section of this essay is called “Future Reading”. Grafton begins by saying that readers need to know how to use both resources, the digital and the physical, as neither one is dying out or becoming the only source for the foreseeable future. Both the physical side of literature and the digital one have pros and cons, and its using those pros that is the talent of modern readers.This reading offers information on the digitization of books in a concise and simple way, giving real modern examples which help overall understanding. It is a valuable source.