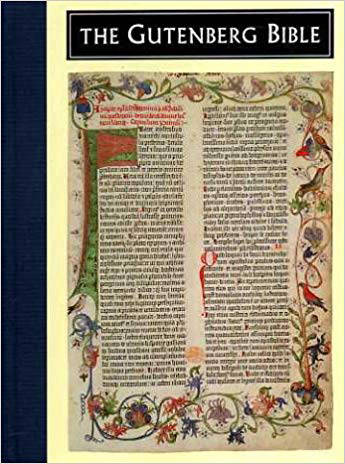

What is a printing press?

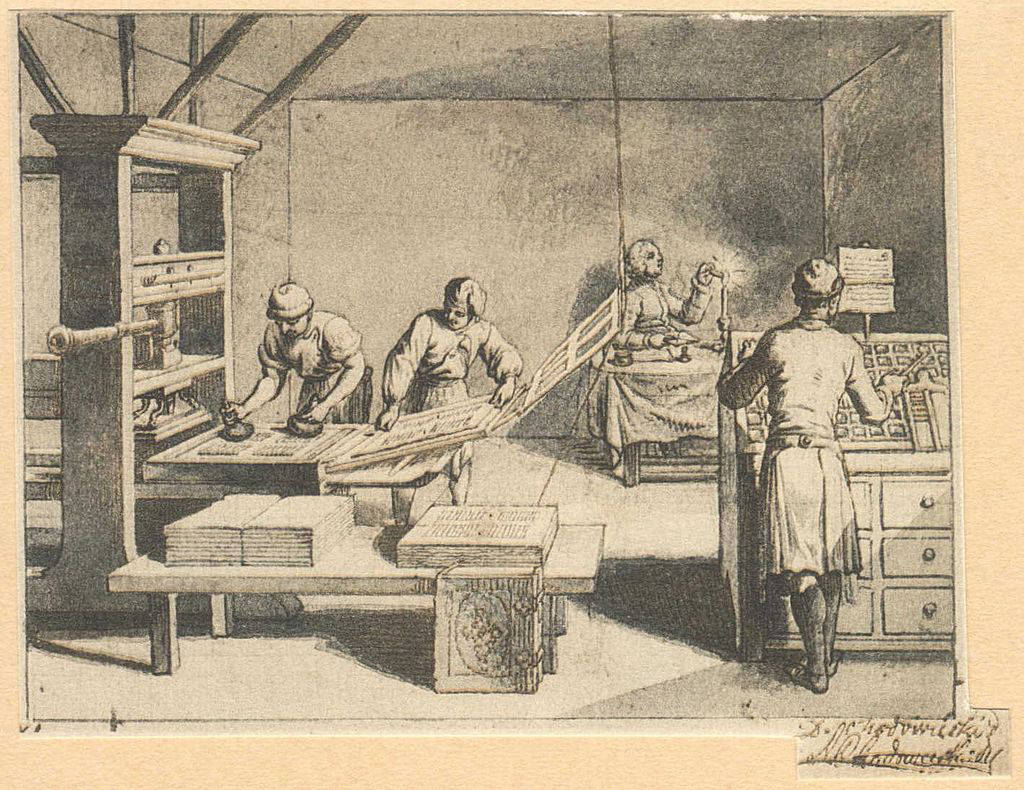

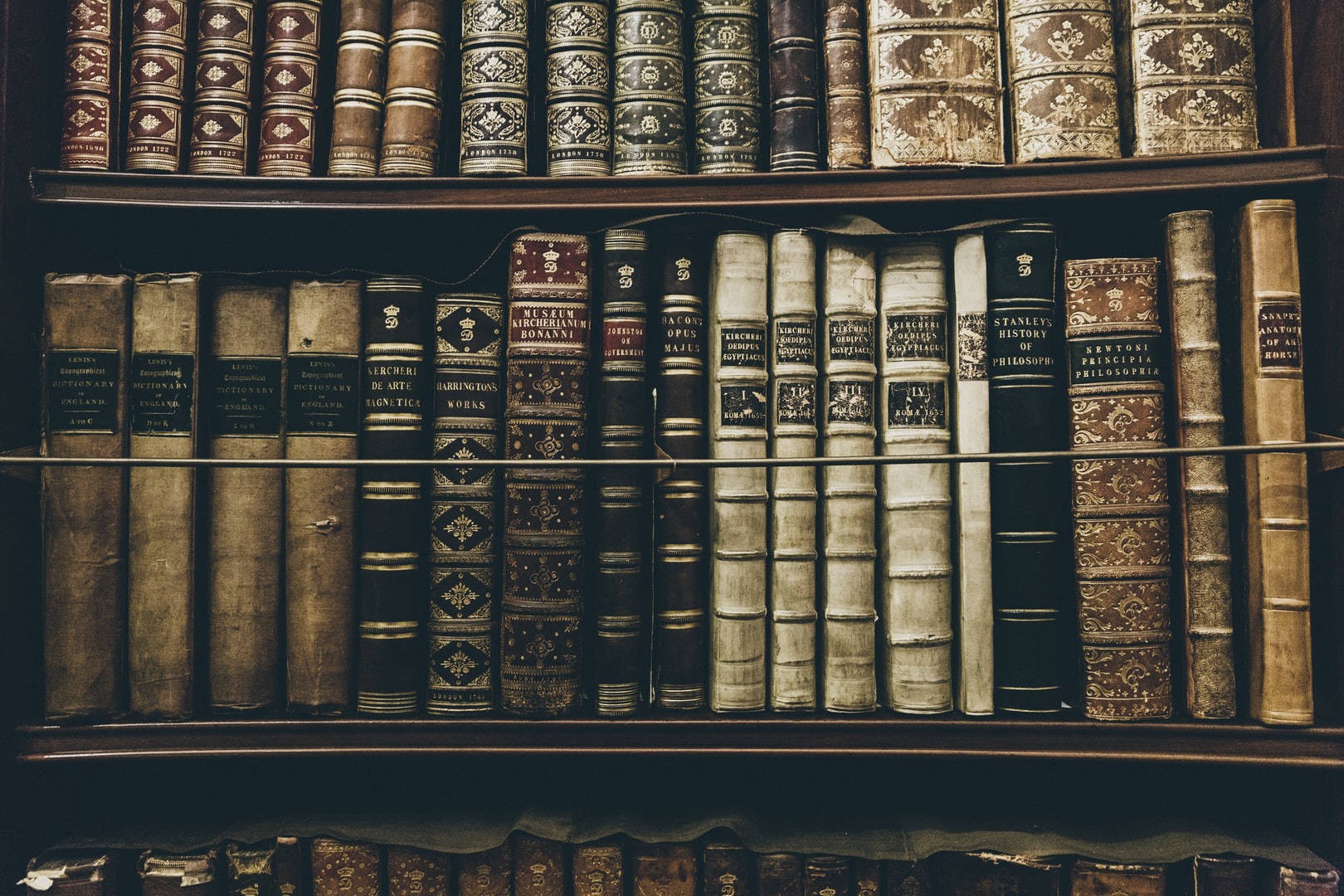

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the cloth, paper or other medium was brushed or rubbed repeatedly to achieve the transfer of ink, and accelerated the process. Typically used for texts, the invention and global spread of the printing press was one of the most influential events in the second millennium.

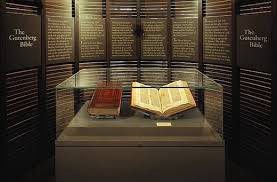

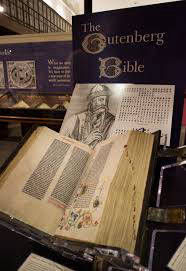

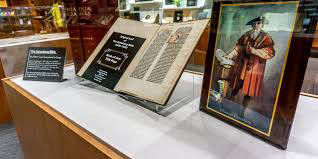

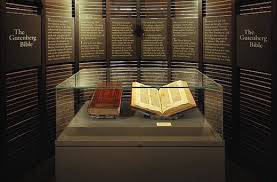

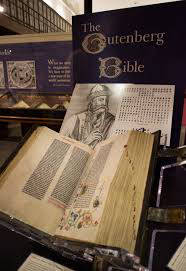

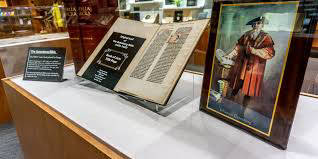

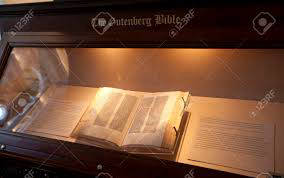

Who Was Johannes Gutenburg?

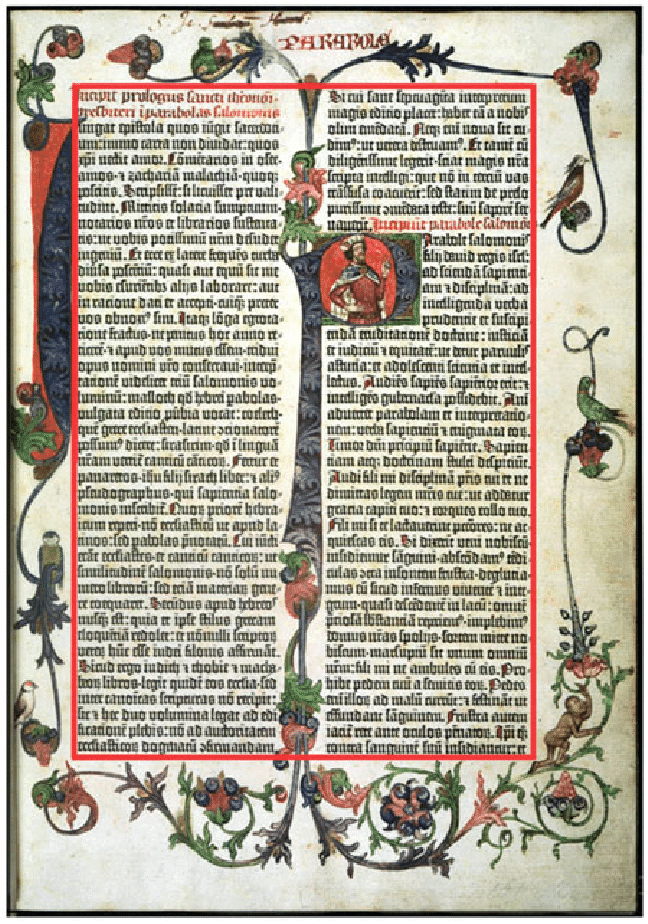

Johannes Gutenburg, a German goldsmith, blacksmith, inventor, printer and publisher was said to have invented the 'printing press' as we know it, in the early 1400's. His introduction of mechanical movable type printing to Europe started the Printing Revolution. It played a key role in the development of the Renaissance, Reformation, the Age of Enlightenment, and the scientific revolution and laid the material basis for the modern knowledge-based economy and the spread of learning to the masses.

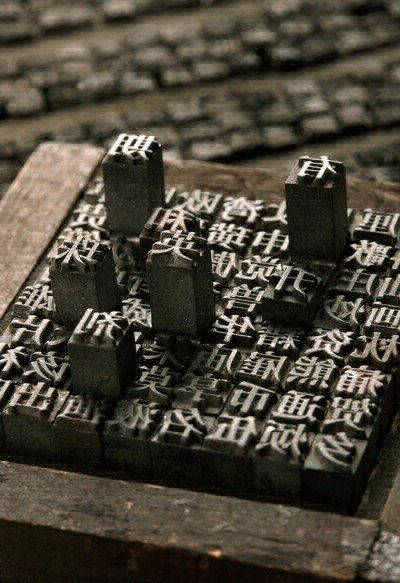

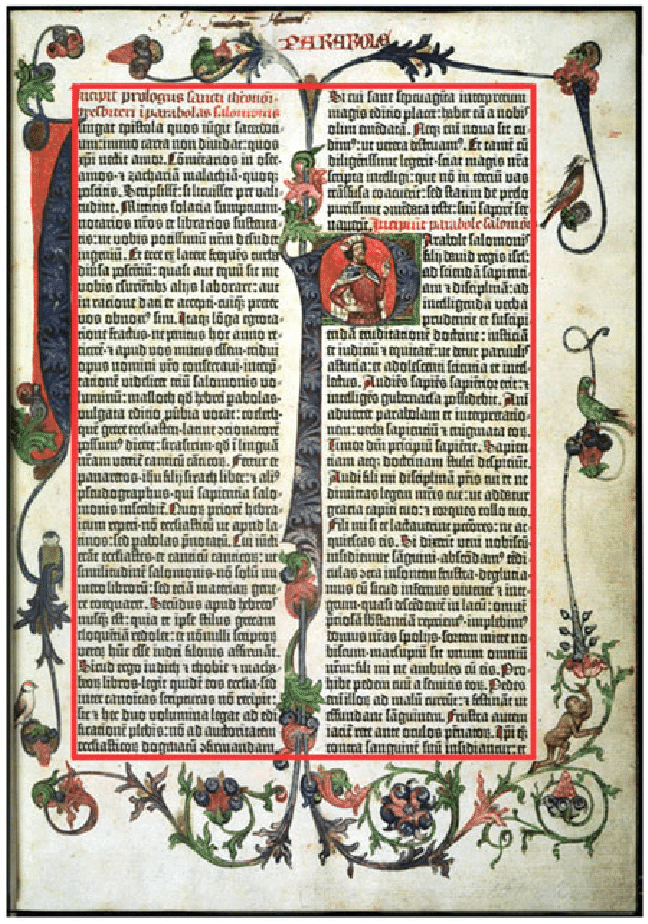

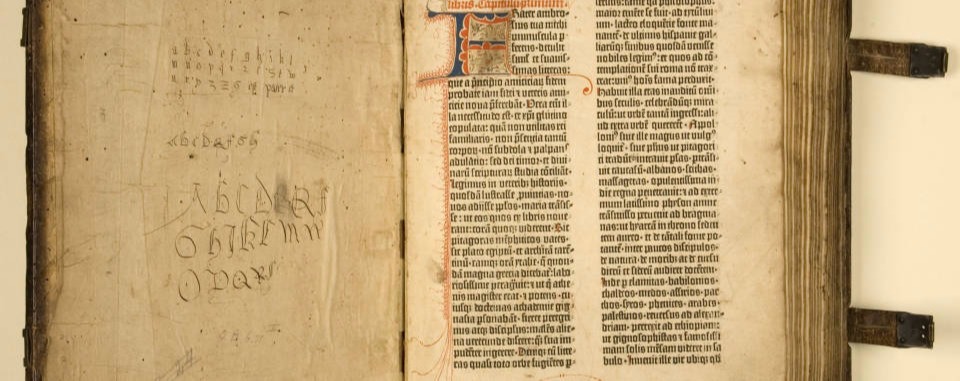

The Signifigance of Movable Type

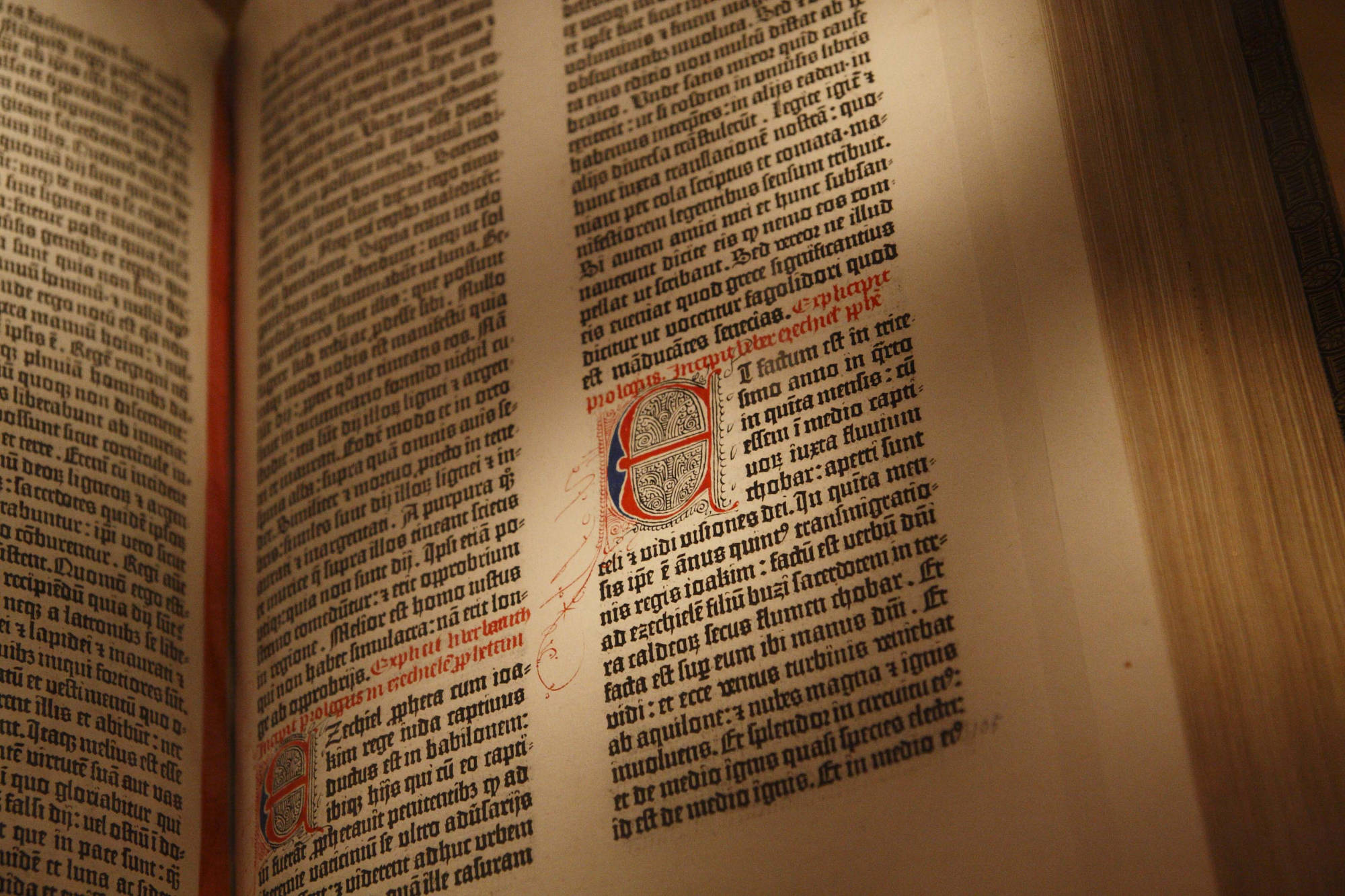

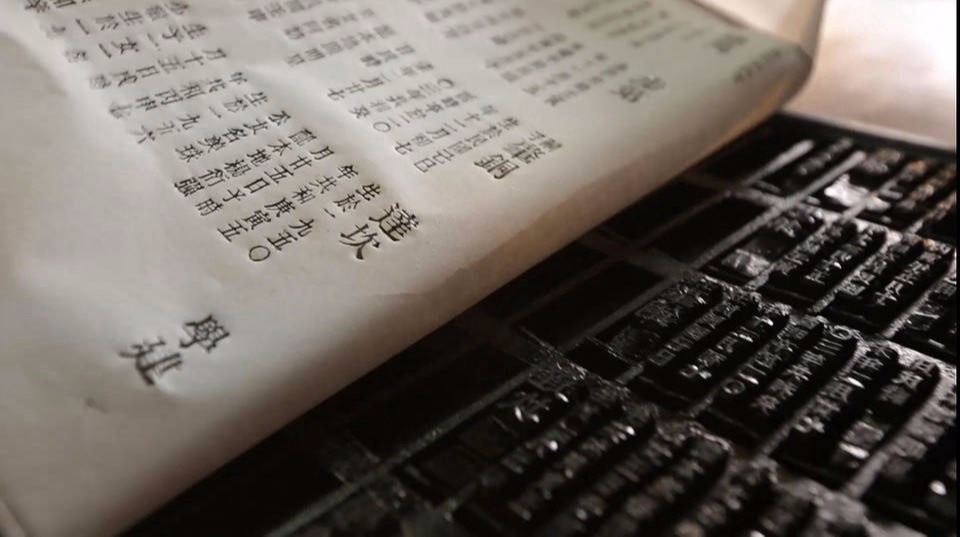

In the standard process of making type, a hard metal punch (made by punchcutting, with the letter carved back to front) is hammered into a softer copper bar, creating a matrix. This is then placed into a hand-held mould and a piece of type, or "sort", is cast by filling the mould with molten type-metal; this cools almost at once, and the resulting piece of type can be removed from the mould. The matrix can be reused to create hundreds, or thousands, of identical sorts so that the same character appearing anywhere within the book will appear very uniform, giving rise, over time, to the development of distinct styles of typefaces or fonts. After casting, the sorts are arranged into type cases, and used to make up pages which are inked and printed, a procedure which can be repeated hundreds, or thousands, of times. The sorts can be reused in any combination, earning the process the name of "movable type".