Books and Print Culture

Welcome! This webpage and the code were all done as part of our great English 2033 class at

Acadia University. As we have learned in class, HTML and other digital mediums

are crucial as the next step in recording, storing and disseminating information in our

society. It is also a lot of fun and is a great skill to learn!

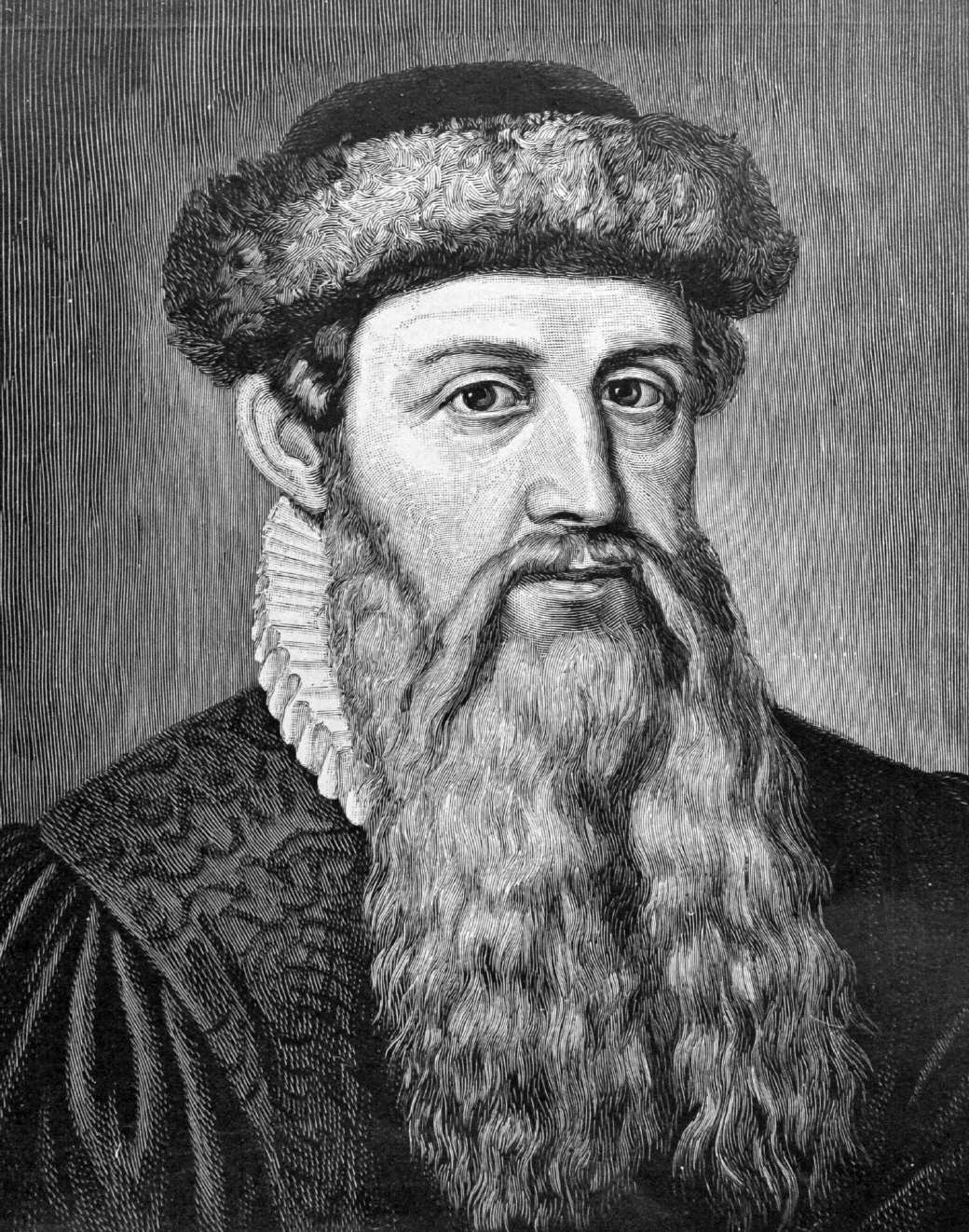

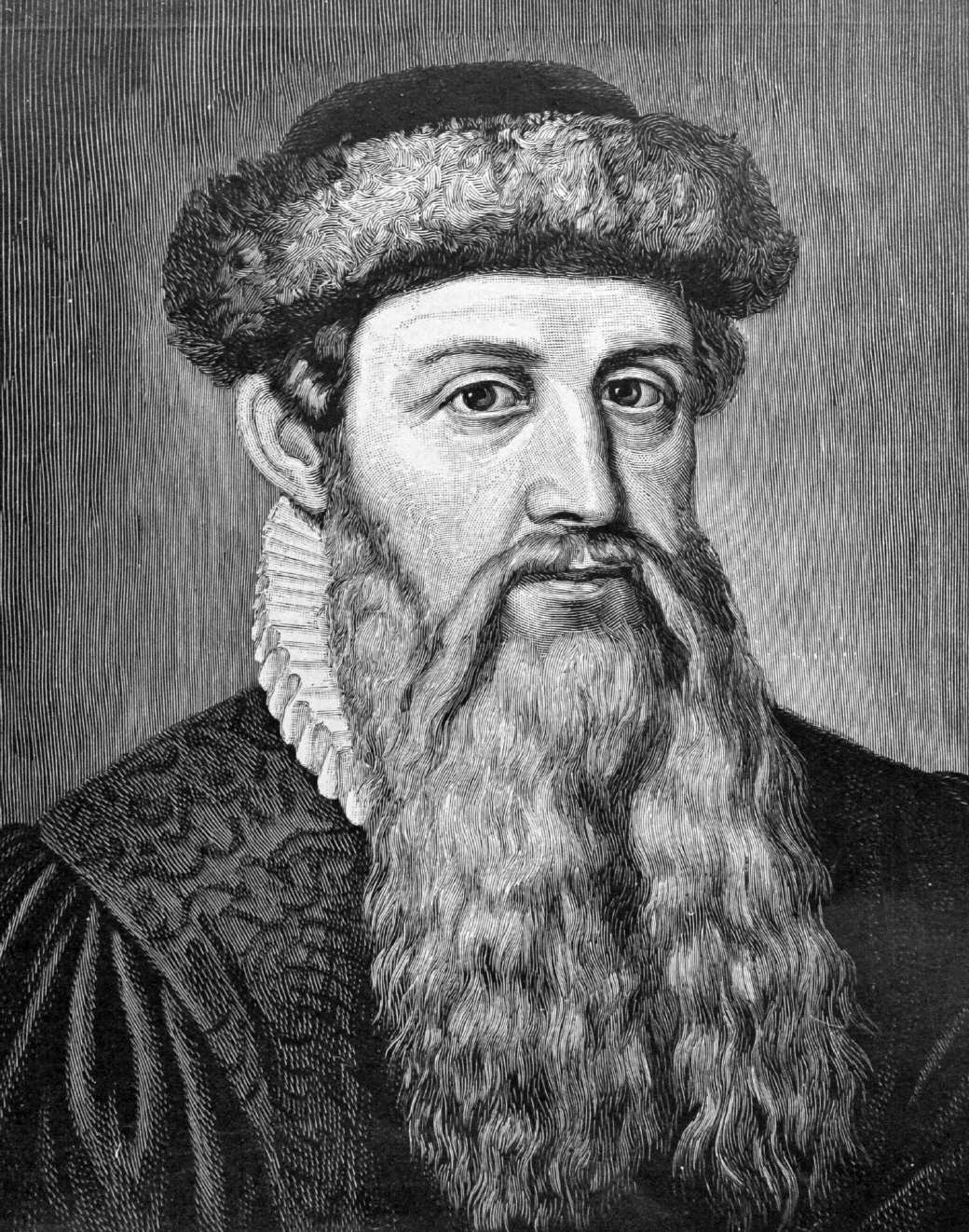

"Yes, it is a press, certainly, but a press from which shall soon flow in inexhaustible

streams the most abundant and most marvelous liquor that has ever flowed to relieve the

thirst of man! Through it God will spread His Word. A spring of pure truth shall flow from

it! Like a new star, it shall scatter the darkness of ignorance, and cause a light

heretofore unknown to shine among men.”

"Yes, it is a press, certainly, but a press from which shall soon flow in inexhaustible

streams the most abundant and most marvelous liquor that has ever flowed to relieve the

thirst of man! Through it God will spread His Word. A spring of pure truth shall flow from

it! Like a new star, it shall scatter the darkness of ignorance, and cause a light

heretofore unknown to shine among men.”

- Johannes Gutenberg, 1400-1468.

Click Here to see our Syllabus

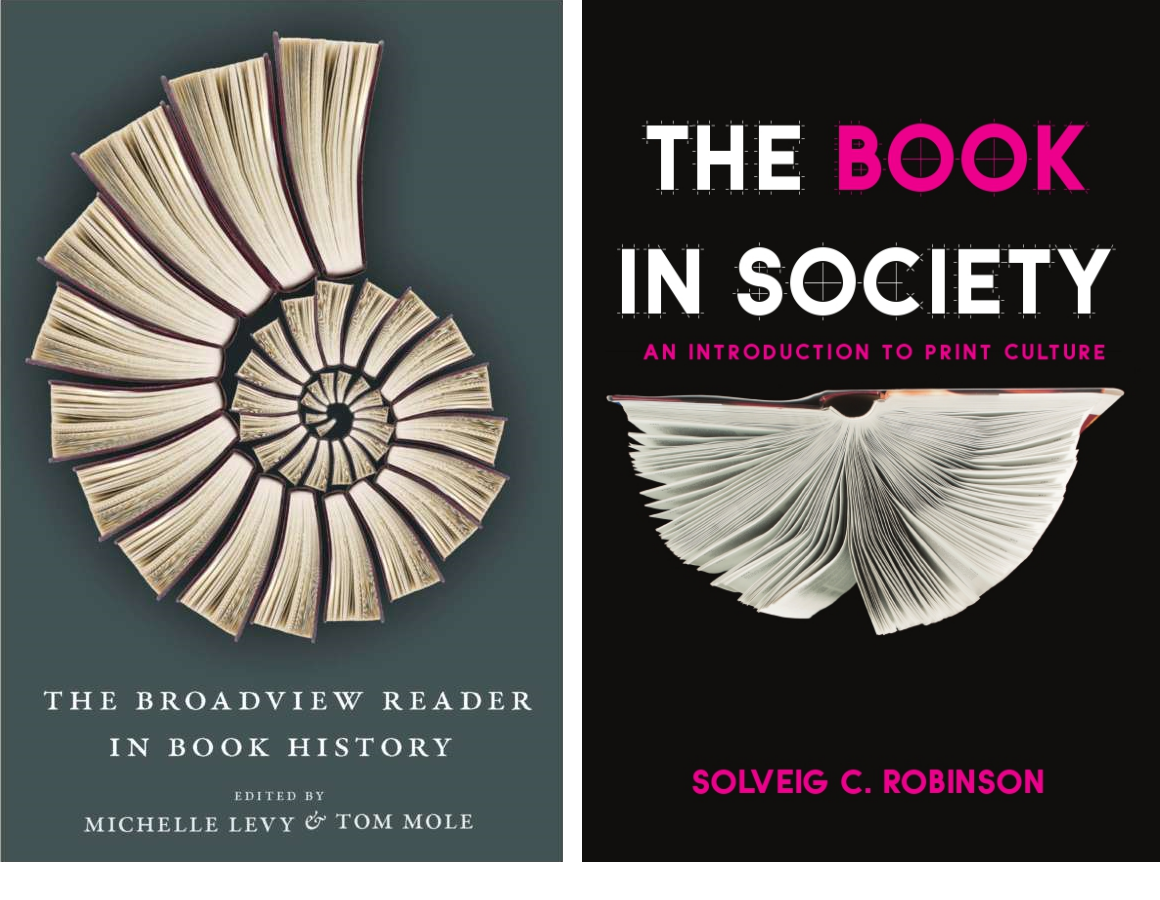

Our readings for ENG 2033:

The Broadview Reader in Book History. Michelle Levy & Tom Mole. Broadview Press, 2017.

The Book in Society. Solveig Robinson. Broadview Press, 2003.

Annotated Bibliographies

Print Culture

"Before printing was discovered, a century was equal to a thousand years.”

- Henry David Thoreau

Greg in Levy 3-12 "What is Bibliography?"

This first essay written by W.W. Greg talks about bibliographies, the study of them and their

significance to literature and books. (At this time it’s like a new field) Greg is basically

addressing the Bibliographical Society here in the early 1900’s making a case for it being a

solid science and speaking to its importance (And not just people who love books talking about

them, actually applying scholarly and scientific method to describing books.) He mentions how

bibliographical study is not just restrained to printed books, manuscripts and even rolls and

papyrus can fit into the study as well. Greg was really trying to show how studying books and

texts using bibliographies to describe texts and what was in them could be an entire school of

study and really was the substance to any good work; its content and sources. He mentions his

love for literature and that's why he really liked bibliographical studies, exposing the meaty

important parts of the text. Greg talked about other fields that are needed for studying

bibliographies for example typology, linguistics, or paleography and how having these skills

are needed, so there is technical skill, however all need critical bibliography. (The science

of the material transmission of literary texts). He ends his text talking about what he hopes

will start being taught at universities around him and the different things that a good

english scholar will look for when looking at literary texts. Picking apart sources, be

critical, anything that is deemed as corrupt or bias taken into account, etc. (Paleography and

Typography are under ‘practices of publication’).

Return to table

Greg in Levy 125-136 "The Rationale of Copy-Text"

Another essay by W.W. Greg, in this one he talks about the importance of editing texts and

preserving as much of the authors words as possible, making sure to push back any changes,

intentional or not, made by others along the book trade process. He goes into the issue with

reliable sources, kind of like in the last reading where he covered bibliographies and sources

but in relation to the “copy-text”. A term he coined but a concept already familiar. The

copy-text is the earlier or original text used to make the new edition. So basically which

texts can we trust? Especially those that have been copied. Problems arise with the

intentional or unintentional changes made along the way, translation for example, our tendency

to rewrite in modern english can take meaning away and thus we usually preserve the original

spelling to show variations in region or time. There's the question of the ‘best’ or ‘most

authoritative' manuscript to trust, having to do with these very problems.

The ‘Tyranny of

copytext” is a concept that Greg brings up as well. He mentions how little changes throughout

the years can affect a lot of change and relying on the original work sometimes changes the

meaning completely. Words and language evolves as well and that must be taken into

consideration when talking about the copytext. The last pages are concerned with the problems

that arise in regards to revision. He says that the editor using the copytext as the original

and changing everything according to it is too “sweeping and mechanical”. He says that for the

most part the original will work well as the model but it is important to know that sometimes

revised editions are better than the originals and its important to know which ones that's the

case for. Greg in the end sums a lot of this up by saying that revisions itself varies in

character and circumstances so it's hard to have a set universal rule for it and he himself is

looking to simply open discussion, not lay down a law for it.

Return to table

Tanselle in Levy 139-154 “The Editorial Problem of Final Authorial Intention"

Here Tanselle is talking about properly showing an author's final intentions and the problems

that arise with that while editing texts. A distinction is drawn between vertical and

horizontal revision and how it can change the intended meaning of a text. Tanselle starts his

essay off talking about how all editors strive to keep intact as much of the authors intent of

the original work as possible. He calls back to Greg’s “The Rationale of Copy-Text” as an

essential part of modern editorial theory, laying down principles for choosing and emending a

text. Tanselle also asks the question of what even the definition of the “authors final

intention” is? He says that the editors task is not to try to ‘improve’ on the text even, if

the author made a bad choice, it is about keeping intact the meaning the author wanted to

convey to their public audience. With this he points out the three different kinds of

‘intention’:

- Programmatic Intention: “author's intention to produce a particular kind of text.”

- Active Intention: “authors intention to be (understood as) acting in some way or other.(which is the intention the author forms in the process of composition to write one word

rather than another.)”

-

Final Intention: “authors intention to cause something or other to happen or other (getting rich, changing minds, etc)”

First is about the general plan to write

a text, second is one concerns meaning in body of work and third is about making changes to

reader for example or making oneself wealthy. An editor's freedom of interpretation is

controlled by his self-imposed limitation. Tanselle brings up Anderson’s A Story Teller’s

Story in which he talks about a typescript print that was edited by three different people,

and so to properly edit the book the editor must familiarize themselves with the type of

corrections, or in this case deletions Anderson would have made. This kind of editing is hard,

especially trying to discern who edited what, although as mentioned some works with multiple

editors come out great such as The Waste Land. So once an editor has separated authorial from

non-authorial alterations (those done by other editors not the author) there is still the

question about how to define ‘Final’. Sometimes this ‘final’ intention is still blurred if the

author has alternative readings and editions floating around or when the entire work itself is

changed in meaning. Some authors as Tanselle mentions even have multiple ‘final’ intentions.

Instead of making one systematic revision it is come back to year after year, evidence of a

changing mind/ideas. In the final pages of his essay Tanselle talks about two issues with

regards to authorial intention:

- ‘What does intention signify, when is it final?’

- ‘Does it matter when the authors wording is recovered, particularly when emendations by others are

improvements?’

These are questions that must be asked when taking on this ‘historical task’

(Which I thought was a very fitting term). The meaning of intention in the end is a rather

philosophical one Tanselle says, although, to do justice to an author one must do justice to

their text.

Return to table

Eisenstein in Levy 215-225 "The Unacknowledged Revolution"

This chapter went over the major advancements in the 20th century in terms of book sales and

rising rates of readership with emphasis on the ‘paperback revolution’ in the 20s and the

‘digital revolution’ of today. It started off talking about education and literacy rates that

had shot up at the turn of the 20th century due to public school implementation in the late

1800s. Many countries were starting to highly value an education for all citizens and this

early education created a whole new generation of readers. The public library system was a big

part of this rise in the reading of books. Public libraries were solidly in place by the 1920s

and offered readers a wide range of material they could rent out for all kinds of purposes:

scholarly, entertainment, for work, leisure, etc. However, more people were reading

periodicals than anything else. Newspapers, magazines, daily, weekly, monthly, quarterly

issues. Periodicals were the dominant print medium in the 19th century. They opened up more of

an avenue for readers in terms of daily reading and one could choose whatever topic they

desired. The Saturday Evening Post originally started by Benjamin Franklin in the late 18th

century took off in the US selling 90,000 copies at the time.

As noted in the chapter, an extremely important part of high readership in the 20th century was the ‘paperback

revolution’.This was in some ways the breaking out from the ‘circulating library’ system

which charged readers per volume to rent the books and would later sell old copies, taking

money away from the authors. It also, perhaps more importantly, had to do with the use of

paperbound books with paper covers. This was a much cheaper alternative and could easily be

mass produced and sold everywhere from gas stations to grocery stores to subways. Penguin

books was a big player that even today is still a large publishing company. Launched in 1935,

Penguin books quickly took to the stage as a very successful paperback distributor and

publisher having authors like Hemingway and Agatha Christie write books under their publishing

brand. The chapter goes on to show the new world of book genres, in particular detective

mysteries and ‘whodunits’ and the ability for authors to pump out novels in a mass production

setting that allowed for millions of people to read their work. The readings end with the

digital revolution and the implications its had on readership and also production of books. As

mentioned, photocopying changed the game in many ways as mechanical typesetting made its way

out.

Return to the table

Darnton in Levy 231-247 “What is the History of Books?"

This reading is tackling the issue of how to study and talk about book history. Darnton

explains his concept of the “communications circuit”, his model for studying the history of

books which connects the author, publisher, printer, distributor, bookseller and reader. It

forms an interrelated circuit that is all connected and works together to preserve and

disseminate information. He explains for example how the reader completes the circuit because

he influences the author before and after composition. As well as how each stage affects the

sale books and thus the spread of information. Darnton focused specifically on the spread of

Voltaire’s work, being a French Revolution specialist himself. He talked about Rigaud, a

bookseller who bought many copies of Voltaire’s works, through the socio-economic lense of the

Annales article that was written on it analyzing book sale trends. He also talked about the

role of the prominent STN (Société typographique de Neuchâtel) which Riguad was a customer of.

The STN was operating in the 1770s and printed many different works to be sent all around

Europe. Darnton mentions the capitalistic aspects of book selling, how business played a big

role in these booksellers inventory. Best-sellers are what they’re looking for and Riguad

seemed to bet that Voltaire’s ‘Questions’ was going to do quite well.

Return to table

Chartier in Levy 251-263 "Communities of Readers"

This chapter by Chartier focused on the ‘ancien regime’ in France which was the period from

about the 16th to 18th century. He covers one aspect of Darnton’s ‘communication circuit’ and

quotes multiple times from Michel de Certeau's works. Both Chartier and Certeau saw the act of

reading and writing as separate, reading being free and writing fixed. He goes on to mention

how reading can be interpreted and appreciated by readers in different ways and its

significance is owed to the reader. Reading does not degrade with time because things can be

read again and forgotten, it does not keep what it acquires unlike writing. Writing resists

time, it accumulates and stays usually in its context if properly recorded. Chartier and

Certeau also discern between different vessels for texts, that is different methods of

recording it. Some texts have different meanings and are interpreted as such, again the reader

affixes meaning through their own reading of a text.

Chartier goes on to explain the amounts

and types of books read by both the rising middle class and the noble class. How texts were

interpreted and even how they were read by different classes. He makes a point in talking

about how there are different ways of understanding text. There are those who are illiterate

and those who are literate which contrast on each other as one can read and another cannot.

However, back in the period of ‘ancien regime’ many people could read but not write, again

showing how these are separate and distinct acts. Some people could interpret lettering

somewhat but mostly relied on images which Chartier says ‘mirrors the text’. Seeing literacy

and readership of books in this way opens up to a whole new group of people that previously

would be overlooked. They too had a relationship with the printed word and print culture and

were also influenced profoundly by it. Another part of this difference in reading and

interpreting text had to do with orally reciting text as compared to reading it over in our

minds. Chartier explains how this is a modern phenomena, reading to ourselves quietly. Back in

the days of scribal culture and early printing days the function of text was to recite it

orally and so that was the way that some read texts by reading it aloud. This as Chartier

shows was cemented as being a part of elite social life as well. He wraps up the chapter

talking about how these communities of readers are ‘interpretive communities’ which affect

meaning and are bound to social difference, they are the ones that attach meaning to what they

read.

Return to table

McGann in Levy 459-473 “The Rationale of Hypertext”

This essay done by Jerome McGann is basically like an update to Greg’s “The Rationale of

copy-text”, he calls it “The Rationale of Hypertext” talking about the future of scholarship

online and digitally. McGann argues that having digital technologies makes the concept of the

‘copy-text’ obsolete. With digital archives, he mentions, both facsimile and eclectic editions

can be brought up at once, not one or the other. (Facsimile editions: “Most useful not as

analytic engines, but as tools for increasing access to rare works.” pg.463) They also allow

for all kinds of mediums at once, such as paintings, songs and written text. (However later on

he also argues for having physical objects in front of you and their merit in a literary

sense.) McGann starts off by obviously giving credit to the ‘information highway’ and the

speed and efficiency of digital information but says that the literature we inherit is and

always will be ‘bookish’. That roughly means that our methods of studying, recording and

keeping old information is based around books and their physical structure. However, we no

longer need books to study the book. Nor is it the most important tool to disseminate and

store information which changes a lot of things in this field. When using a book to study

books there is a limit to the analyses one can make, because they are contained to that

medium, such as: descriptive bibliographies, apparatus structures, etc. So for example when

the reader wants or needs something beyond just the text like hearing a song or ballad, seeing

a play or just physical features of something. The full power of logical structures is

constrained by the bookish format. As McGann puts it: “The archives are sinking in a white sea

of paper”.

Getting into hypertext and hyper editing now, McGann starts to talk about editing

through computers and the implications. Big projects have already been around such as COLLATE

for hyper-editing and analyses of manuscripts and such, and again the speed of computers

changes things so drastically here. McGann’s ideal final goal would be a networked hypermedia

archive, although there are many problems that would be too much to talk about here he

mentions. Hypermedia is information displayed in multiple mediums, not just semantics, the

three pointed out are: language visible, auditory and intellectual. William Blake is brought

up as an example where a hypermedia archive would suit his work well, even mentioning

something along those lines is already on the way. He goes on to show how some of Dickonson’s

work like a poem she wrote: “Alone and in a Circumstance”, she wrote it in a space she made

under a stamp of a locomotive which added a visual piece to her complete poem. She added an

artistic addition, not literary one and because it was an uncancelled stamp it could be easily

reprinted. This showed how she disagreed with the ‘auctioning’ of print publication. McGann

finished his essay off talking about the Rossetti Hypermedia Archive and all the challenges

and questions that might arise from using hypertext to record and study literature. He

mentions how “when a book is produced it literally closes its covers on itself,'' referring to

the fact that the hypermedia archive will not have later additions but can be continuously

updated and made longer. Whichever way you cut it, however, digital sources just are quicker

and bigger than any paper edition could ever hope to be.

Return to table

Hayles in Levy 491-508

This essay by Katherine Hayles, an expert in literature and chemistry, is about reading in the

modern age in relation to digital vs. printed material. Hayles argues that the shift from

print to digital has changed reading and cognition in us. WIth the rise of new technologies,

we must rethink what reading is, how we absorb literature and in what medium and volume.

Hayles also theorizes new ways of reading like hyperreading and machine reading that make

online databases so fast and computational. She mentions the different trends of reading for

that time, with downward trends of printed material (poems, plays, novels) but a rise in

reading in general from junior high to grad school. She also brings up the concern of lowering

reading rates and lowering reading ability and vice versa. “The two tracks, print and digital,

run side by side, but messages from either track does not jump to the other side.” (Hayles,

493). Close reading in the following pages is covered. As Hayles and others agree close

reading is what “transformed cultured gentlemen into a profession” it is stapled down as a

major study of literature and being the only real method to rely on to prove the literary

studies worth in society. She also contrasts it with ‘symptomatic reading’ and its

implications as a contemporarily dominant close reading technique.

From here she gets into

digital and print literacies. University students are a strong reading demographic and the

stats show they’re moving towards more digital than anything; so the question is how to apply

good reading techniques that one would acquire from printed reading? From here she goes into

the differences between hyperreading and print reading and the differences between the two. In

a study done, the movement of eyes tracked of a person reading a webpage showed they read in

an “F” pattern and as they moved down they read in a vertical form reading the left hand

material. This showed that webpage reading is sloppy to the max. Close reading and hyperreading

are not on the same track according to Hayles. However search bars and machine searches are a

valuable part of archivists or scholars toolkit. Some like Nicholas Carr think that

hyperreading is processed differently in our brains and thus leads to shortened attention

span, causing us to skim over everything. (Not too far a cry from social media users today).

Another study Hayles brings up is in the ‘Reading on the Web’ section of her essay. In this

study two groups were told to read “The Demon Lover’, one with print and the other with links.

The first group out performed the others in comprehension of plot and said they enjoyed the

story more as well. “Increased demands of decision making and visual processing” was one of

the conclusions reached. Another factor is the ability to create new neural pathways by

repeating things, when scrolling or moving less is retained than a simple physical page turn.

As Hayles goes into her second last section ‘Anecdotal Evidence’ she talks about the stories

told to he about other students, for example. How many teachers were telling her that they no

longer assign long chapters because students don't retain it well, so short stories are used

more now. Hayles hypothesizes a shift in cognitive attention. At the end of her essay she ties

everything up nicely by talking about the similarities between digital and print and the

advantages of the latter. As she mentions “Reading has always been constituted through complex

and diverse practices. Now it is time to re-think what reading is… in the rich mixtures of

words and images, sounds and animations, graphics and letters.”

Return to table

Grafton in Levy 555-572

Codex in Crisis: The Book Dematerializes:

Alferd Kazin, writes book on American intellectual and literary movements from the 19th

century “Without leaving Manhattan Kazin read his way into ‘lonely small towns, prairie

villages, isolated colleges” The book as it becomes digitized in our modern world Emphasis on

Google Books as an example, pros and cons of using this kind of system Dreams of a ‘universal

archive’ or database that could contain “entire history of the human race” The author believed

competent government can do a better job than markets in some cases in making books and

information available to the public

The Universal Library:

Comparing the library of Alexandria with Google Books. Library of Alexandria was founded in

300 BCE, started collecting Greek literature. Confiscated all scrolls that came in ships, made

copies and gave them back to the owner. They developed new methods of bibliography, philology

and categorizing their books. Like Google the library of Alexandria developed a good method

for reproducing and capturing texts.

Googles Empire:

Here Grafton talks about Google, its origins and uses. Started as a project to have a database

for books in stanford 95% of scholarly inquiries start with Google. As Google, Amazon, Barnes

& Nobles, etc compete, the internet has become a vast bookstore. Everyone also has access to

computers more or less so it is a very universal and global thing. The Google Library Project

→ partnered with big libraries, Stanford, NYC, etc.

116 Million Books → 60 Million Brits. 36 Million Books → 1.1 Billion Indians. “World poverty…

is embodied in lack of print as well as lack of food” (562).

However this is getting better, more access in remote regions. “The mass of old and new texts

on the Web will not be an English-only-zone”, there are lots of other languages already. There

are also errors that will come with digitizing libraries. There is no unified single database

for early works and literature; rather a patchwork of different databases and archives →

Google nor other companies have found the solution to amassing everything together but

accessibility is still going up as time goes on. Since the digital revolution we have come to

understand what makes physical archives and libraries so distinctive and useful → Simple ex:

You want to see a document of a commanding officer in the Air Force, you must have the proper

paper to show it is genuine, not just the plain text → For spotting important physical aspects

of a book, no image can do the justice of having the physical thing in front of you. (Smell

it, see it, feel it, TASTE IT?). Watermarks, Binding, Marginalia → multiple copies of texts,

manuscripts, and so on. These are all essential to a deeper understanding of the works and

provide important background on the individual.

Publishing Without Paper:

It's not just research that's changing, writing and publishing as well “Revolutions are

caused… by raising expectations” (569). Increasingly less articles in paper being read,

students chose digital media. Many big Universities like Harvard are getting their faculty to

publicly post their publications. Using digital archives has many pros however, search engine,

hypertext, etc. New media of the 1900s transformed things just as much as the internet,

newspapers in Berlin could have printed papers in 18 minutes after getting the news at the

central office. Not as flexible or high speed as the internet but the mix of serious and

funny, provocative and everyday → created new culture and ideas, changed communication among

towns and cities. Some say libraries doomed to ‘extinction’. New digital sources are being

read differently, average of 4 minutes spent on e-book sources.

Future Reading:

We should not avoid the ‘open road’ that leads to an ‘electronic paradise’ (572). To really

get a physical feel however libraries fill that distinct need. “Knowledge is still embodied in

millions of dusty, crumbling, smelly, irreplaceable… books” (572).

Access is important → Really nails down the importance of digital reading. We need to shape

digital practices to those of the physical library.

Return to table

"Yes, it is a press, certainly, but a press from which shall soon flow in inexhaustible

streams the most abundant and most marvelous liquor that has ever flowed to relieve the

thirst of man! Through it God will spread His Word. A spring of pure truth shall flow from

it! Like a new star, it shall scatter the darkness of ignorance, and cause a light

heretofore unknown to shine among men.”

"Yes, it is a press, certainly, but a press from which shall soon flow in inexhaustible

streams the most abundant and most marvelous liquor that has ever flowed to relieve the

thirst of man! Through it God will spread His Word. A spring of pure truth shall flow from

it! Like a new star, it shall scatter the darkness of ignorance, and cause a light

heretofore unknown to shine among men.”